A bitter mistake.

By sheer chance, a simple, banal, and unfortunate bump in the road, our dear Weekly Shonen Jump has once again committed one of its terrible blunders. It doesn’t happen that often. After all, the biggest manga magazine in the world tends to keep a steady pace, and its little slip-ups are usually, well, little. But every now and then they do happen. When they do, human nature kicks in. We unleash disproportionate cruelty, take pleasure in highlighting tiny mistakes, ignore years of consistency just to point out hypocrisies and incoherences, and prove that the guy who usually gets everything right finally messed up. There it is, caught red-handed.

Throughout such a steady 2025 filled with guaranteed flops, Shonen Jump finally perpetrated one of its annual accidents. It was the biggest misfortune possible: the controversial release of a good story. It’s hard to believe. The moment we spot such an error, we start doubting its very existence, seized by instant disbelief. In terms of vibes, style, and intent, none of it feels very Shonen Jump. It’s such an out-of-place story that we naturally question everything. Is this thing actually good? Can it work? Will it last? Will it sell? In Jump? Are you really sure people will like this? Inevitably, suspicion takes over.

The biggest and best website covering Japanese comics, which you are currently on, stays packed with articles dissecting sales, describing receptions, offering retrospectives, and analyzing TOCs. These analyses often serve as good projections for visualizing the short-term future of its manga. In other words, we cover the past, present, and future very well.

What’s missing is talking about stories for the sake of stories. We owe a debt in the department of meticulous observation, in the attention to what truly captivates us: manga itself. It sounds obvious, but introductions need to be obvious to wake up the inattentive. The time has come to analyze the biggest mistake Jump made this year. So used to releasing junk, stories that make you doubt editorial professionalism, the sanity of their creators, and the patience of their readers, the magazine let a quiet little offender slip in. It remains discreet, yet so coherent in its intentions, presenting subtleties that require a more attentive look. As Thomas Hobbes once said, man is born funny, and society corrupts him.

How to be funny

There is no fictional genre more complex, variable, and convoluted than Comedy. Perhaps Horror comes close, although it faces more resistance and appears far less often in our daily lives. We seek one and avoid the other. Comedy infiltrates many aspects of life, from the most casual to the most professional. Its superiority becomes evident through this simple observation.

Rare are the situations where being funny becomes a problem. Aside from tactlessness in sensitive moments, comedy and laughter are nearly always welcome. Even in inappropriate situations, comedy often gains double strength, precisely because unpredictability is one of its core elements. Laughing at what we shouldn’t laugh at is often extremely funny. It sometimes feels as if humanity is destined to joke about everything its social environment allows. For some, breaking those boundaries becomes even more hilarious.

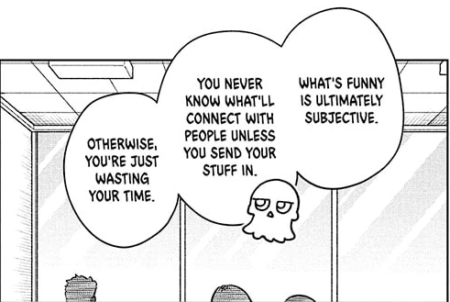

So why do we laugh? What makes something funny or not? The laziest and most superficial answer is always the same: “it depends, it’s subjective.” It is a lazy answer, but no one will deny that deep down it works exactly like that. Everything does depend. But is there anything in life that does not? We can dig deeper than the surface. Certain subjectivities accumulate so strongly that their consensus forms a kind of objectivity. This becomes clear when we study history, since the attempt to objectify humor and laughter is not new.

Aristotle was already pondering laughter back in Ancient Greece. In the Western world, comedy was born in Greek theater. By the 19th century, philosophers like Henri Bergson were picking apart the peculiarities of laughter. Kant and Kierkegaard also left important reflections on the topic. When you realize that a bunch of old bald men who called themselves philosophers, and that many smartasses read in order to understand what other smartasses are talking about, were all trying to explain what causes laughter and what comedy is, you realize the topic is no small deal.

But careful. This is a Western approach to comedy, and we’re talking about an Eastern artistic piece that operates through different cultural mechanisms. How useful is it to analyze Japanese comedy with such a distant mentality? Not very, although not entirely pointless.

In the West, we have stand-up, a one-man show where someone tells stories and jokes. This isn’t common in Japan. Traditional structured humor there is found in Rakugo and Manzai. You already know Rakugo if you read Akane Banashi. You probably also know Manzai, a duo consisting of a Boke, the fool who causes trouble, and a Tsukkomi, the straight man who corrects him.

Sharp political-social critique appears far more strongly in Western comedy, while surreal nonsense humor plays a much more relevant role in Japanese comedy. The gap is clear. Japanese humor is not “our” humor. Part of its charm lies precisely in that difference. Of course, this isn’t absolute. People naturally seek familiarity, which is why romantic comedies and action comedies are far more popular here than pure nonsense comedies.

What makes manga so captivating for non-Japanese readers is precisely this distance. We realize we’re reading something that isn’t “our way” of storytelling. Our experience with Japanese works is not the same as a Japanese reader’s experience. But does it make sense to be so blunt while analyzing a story built on subtlety? Maybe I drifted into basic anthropology, but we needed this mental reset to find the answer that Someone Hertz so intensely seeks.

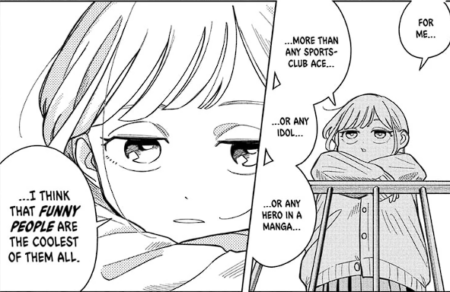

Despite cultural differences, we share a common point: we are all fascinated by laughter. We love comedy. We want to laugh, to make others laugh, to be funny. Both here and there, although through different paths, we seek comedy. Being funny is the coolest thing possible.

Comedy, all the same?

Our protagonist Mimei Fukumori is a diligent and competent student in many areas of his life. He is good athletically and intellectually, but he cannot master the most important skill in every young student’s life: being funny. The boy is addicted to a popular early-morning comedy talk show. Every week, the hosts describe a hypothetical scenario. Listeners must respond creatively and humorously. The best submissions are selected and read on air.

Funny? Maybe. It depends, as you may insist. But we will have time to highlight Someone Hertz’s peculiarities properly. Before that, let me resort one last time to listings. Truly the last. Please be patient and follow me through this final classificatory invention. We can divide comedies into types.

Nonsense comedy. A Japanese classic in which madness runs free without clear reason, and events unfold in surreal, illogical ways. The humor lies in breaking expectations and embracing unpredictability. The absurd may start in reality and end in chaos, or start chaotic from the beginning.

Manzai comedy – Another Japanese classic centered on the contrast between the serious and the foolish.

Acid comedy – Focused on social critique and irony directed at political and social issues.

Embarrassment comedy – Humor derived from teasing, physical hits, and humiliation.

Now, remember the word I used at the start of the text, “convoluted.” I didn’t use it only because it’s fancy. I used it because it’s appropriate. Something convoluted folds onto itself or around something else. No comedy is only one thing. Comedy blends different kinds in different degrees. How would you classify Gintama or Witch Watch using this silly system? Witch Watch can be nonsense one moment and serious the next. Morihito can be the composed guy and also the featured idiot. The series mixes fights and romance within the same chapter. It’s a glorious fruit salad.

So what was the point of listing “types” if every comedy blends several anyway? I didn’t do it just to stretch the text. I did it because Someone Hertz has such an acute sweetness that appreciating it requires training your palate with many flavors. What makes its story delicately unique in such a competitive comedy landscape is its rare “type” of humor, a style that is subtly funny and naturally cute.

The gentle art of comedy

What Someone Hertz delivers is a completely unique subtlety. No other word suits it better. The nonsense element appears in small doses. Aggressive slapstick is nonexistent. Acidic humor is absent. What remains is romantic comedy and manzai elements. This combination is simple and classic. If that were all, the manga would be ordinary. But the crucial ingredient of subtlety transforms this carbon structure into a beautiful diamond.

Kurage, our co-protagonist, is the goal of our protagonist. If being funny is the mission, we want to resemble the funniest person in the room. We want to be like the Eel-Potato. Kurage does not try to be funny. She simply is. Being effortlessly funny means being Kurage. You probably know someone like this, always ready to make you laugh in any situation.

Some people are just like that, born with talent. But then comes the CR7 vs Messi dilemma, Rock Lee vs Gaara, Vasco vs Flamengo. Can hard work beat talent? Does talent even exist, or is it another form of unconscious effort? Is there a comedy gene? Is it recessive or dominant?

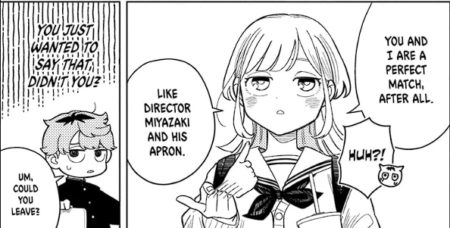

Someone Hertz is subtle and gentle. There is no humiliation-based humor. Everything Kurage does comes from silly puns, pop culture references, and quirky observations. The paneling prioritizes close-ups, especially of Kurage, whose face often appears inches from the “camera.” This decision emphasizes her strange sense of distance from others and highlights what matters most: her overwhelming cuteness.

That cuteness is one of the keys to the series’s success. With such discreet comedy, cuteness bursts openly. It is the yeast that makes the dough rise. The story may not have hyper-inventive paneling, but it offers clever, lightweight visual choices that compensate for its simple art through personality. If the artwork is merely functional, the writing has room to shine even more.

Its publication context also helps. Shonen Jump has a very defined identity and a deeply rooted image in readers’ minds. Yet within that normality, small offenders are welcome. Blue Box, Ruri Dragon, and Akane Banashi are huge hits in a magazine used to a different tone.

Someone Hertz does not fit the usual visual or narrative mold of Jump, but it works. Of course it does. Readers love embracing things that feel new, even when they aren’t truly new. The motto “friendship, effort, victory” remains. Only appearances change. You won’t immediately picture Someone Hertz when thinking of Shonen Jump. Not only because it is new, but because it doesn’t match the stereotype of what Jump is. That is excellent. It strengthens its uniqueness.

Someone Hertz is a delicately crafted work. It captures the casualness of daily life and the ability to build bonds through humor. These are the silly jokes you exchange with that friend who loves teasing you, and you love teasing back. Here, the growing romantic tension between the two teens makes the story even more delightful.

Being able to approach others, to be seen, to explore artistic potential through casual laughter, even with a small side smile, shapes a comedy that does not want to be traditional. It wants to be discreetly different. This subtle distinction makes the series so attractive to an audience numbed by sameness. It does not try to reinvent the wheel, but it refuses to be mediocre.

Calmly and quietly, Someone Hertz entertains you with an unexplored type of comedy. It becomes something quietly original in its environment. It often does not make you burst into laughter, but emotion does not always need to be loud. You don’t only have fun when you laugh until you choke. Sometimes a simple, casual joke softens your bitterness and brightens your day. A sequence of small smiles can satisfy as much as one big laugh.

The shared growth of two teenagers who love the same hobby beautifully idealizes school youth. It portrays mutual growth and the blossoming of affection, something I, poor miserable ill-mannered soul, never experienced. It is wonderful to see through art what feels so distant from us.

With its unpretentious, calm, and comforting writing, Someone Hertz creates a microcosm of the comedy that permeates our daily lives. It is everywhere and yet rarely represented. It goes against the urgency for grandeur. Its path is gentle. It feels like that cute video of a kitten jumping and scratching itself. Unless you are a psychopath, it won’t make you roar with laughter. Instead, the soft smile and the soothing sensation that follows, in the long run, will be wonderfully equivalent. Will you like the series? Will you find it truly funny? Of course it depends, but not only.

Article translated from Portuguese.