It’s not uncommon to see Western comments questioning the continuation of Nue’s Exorcist (Nue no Onmyouji) in Shonen Jump. The manga is one of the least popular in the magazine’s lineup on MangaPlus and has always been controversial among many readers, who consider it “generic.”

However, the situation is quite different in Japan, where Nue ranks in the magazine’s upper half in terms of sales, surpassing more traditionally styled battle series like Shinobigoto and Kiyoshi-kun. Its circulation puts it above 100,000 copies per volume, it won AnimeJapan’s “manga I most want to see animated” award, it has collected praise from famous authors in the industry, and it receives more merchandise than any other new non-animated series aside from the giant Kagurabachi. What explains such a stark difference?

BUT WHAT IS NUE’S EXORCIST?

To begin, let’s introduce the story and the basic structure of the manga for those unfamiliar. Gakuro Yajima is a typical shy Japanese student, but he can see spirits. Upon meeting a mysterious woman (Nue) at his school, he forms a contract with her that grants him her powers so he can fight these beings. Over time, Nue’s goal is revealed: to exterminate the Hyo, powerful spirits highly dangerous to humanity.

Sounds like the plot of a typical battle shonen, right? But here comes the second aspect of the manga: it’s also a romantic-comedy harem. Each arc in Nue centers around a new heroine who gets involved with Gakuro; together they grow closer and even face enemies. The chapters alternate basically between slice-of-life moments, romance, and battles.

Nue is popularly seen as part of the “battle harem” genre — a subgenre of manga, anime, light novels, games, etc. defined by typical battle-story plots blended with romcom elements, but with the added point that the heroines take an active role in the action, having powers and combat ability similar to the protagonist.

In Shonen Jump itself, works of this type are rare in its history. The editorial department values works with mass-market appeal, preferring more traditional battle series. Harem manga appear in Jump occasionally, but without this kind of combat. Examples include Ichigo 100%, To Love-Ru, and the current Hima-ten.

However, defining “battle harem” depends on how balanced the elements are and whether they lean too heavily in one direction. In Katekyo Hitman Reborn, there’s a secondary plot where Tsuna is the romantic interest of both Kyoko and Haru, but the two girls aren’t fighters and the story eventually focuses far more on epic battles. In Ayakashi Triangle, there’s a romance between ninja Matsuri and his childhood friend Suzu, but despite having battles, it was seen more as an ecchi work than an action one.

The closest “modern” example I can think of is Nurarihyon no Mago, which even has a trio of heroines — Tsurara, Yura, and Kana. However, the focus of that manga is definitely action.

The clearest examples of the battle harem come from outside Jump, such as Negima, High School DxD, Tenchi Muyo, etc. But the two mediums that most often produced works of this type were Visual Novels and Light Novels. Among many titles, two series stand out as direct narrative and structural influences for Nue: the duo Fate/stay night and Tsukihime (from author Kinoko Nasu), and the To Aru franchise by Kazuma Kamachi, which includes A Certain Magical Index and A Certain Scientific Railgun, among others.

Nasu’s influence is directly seen in the mix of romance with multiple heroines amid an imminent apocalypse looming over Gakuro’s everyday life. The Hyo are awakening, and their rise would end everything he knows and all the people he loves. This supernatural side has something “chuunibyou-like,” with monstrous designs and attacks using unusual ideograms and complex names—even for Japanese readers.

Narita Ryohgo, author of Baccano, Durarara, and Fate/strange fake, is a big fan of Nue and has praised this atmosphere where you need to read the furigana above the weird kanji used in the series’ attacks. This element was common in VNs and Light Novels in the 2000s.

Structurally, Nue borrows more from To Aru. In VNs, players choose a heroine route to follow until it ends in a romance. Light novels adapted this multi-romance element into a linear narrative, focusing instead on rotating heroines by arc.

In Index, this is obvious: the first three arcs follow the pattern of a central girl being the focus of the story, while protagonist Touma gets involved with her and dives into action because of that connection. In the Index arc, it’s Index; in Deep Blood, Himegami Aisa; in the classic Sisters arc, the popular Misaka Mikoto.

In Nue, it’s no different: the Fujino Family arc focuses on Shiroha; the Village arc on Shitotsu; the Suzaku arc on Ishu, etc. There is always a connection between the new heroine being developed and the upcoming action.

Author Kota Kawae doesn’t hide his countless references (including figures of Saber from Fate and Misaka Mikoto from Railgun appearing on panel), so this side — directly influenced by 2000s otaku works — resonated with many fans and industry creators who appreciate aspects of that era, seeing Nue as a return to a structure that faded with the rise of isekai light novels and mobile games, which took over much of that otaku niche space.

With many comments joking from the beginning that Nue feels like a PSP visual novel adaptation, Jump seems to have embraced this identity. The magazine recently made a mini romantic VN featuring the series’ girls.

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES

With all that explained, let’s get into this part of the discussion. It’s undeniable that the development of anime and manga culture varies across the world based on factors like:

-

When it was introduced

-

Which works introduced it

-

Fan culture

A good example: Saint Seiya is seen as a foundational anime in Brazil. It arrived early and introduced many of the main elements of battle shonen to Brazilian audiences: the power of friendship and perseverance, protagonists who always stand back up, the “one stays behind to fight while the others advance” arc structure, etc. It marked an era and remains influential among Brazilian fans.

In contrast, the U.S. started getting into anime later, already having Dragon Ball Z before Seiya. Thus, Seiya never developed the same strong identity among Americans. Many encountered these themes through later works directly influenced by Saint Seiya, like Bleach.

Meanwhile, Brazil entered the tokusatsu world through shows like Jiraya and Jaspion, which are pillars of the genre there — but not in Japan, where the cultural identity of the genre lies with the early Kamen Rider and Ultraman. It’s to the point where actors from those series say they’re more recognized by Brazilians than by Japanese fans.

But where am I going with this? Simple: Japanese anime/manga fans who grew up in the 1990s and 2000s had greater access to the “Akiba-kei” otaku culture. It’s a somewhat vague term that describes the style of Akihabara’s otaku district, but is heavily associated with the more niche side of several industries appealing to a dedicated, slightly older audience who loved a variety of associated subcultures: idols, maids, VNs (dating sims), niche anime/manga, cosplay, doujin works, etc.

In the shadows of Shonen Jump’s mainstream—publishing Japan’s biggest hits in the 1990s and 2000s like Dragon Ball, Slam Dunk, and One Piece—Akiba’s subculture created its own icons, subgenres, and narrative elements. There was still crossover, of course, since it’s the same industry; Love Hina was published in Shonen Magazine and brought much of the “bishoujo” (beautiful girls) dating-sim culture into a mainstream shonen magazine, becoming extremely popular and influential. But Jump itself has always sought works with the broadest mainstream appeal.

To Love-Ru was a very popular ecchi manga within these circles in the 2000s, but according to legend, its low TOC ranking in Jump was strategic regardless of votes. The manga sold well, and its goods sold like water in the desert among otaku—generally older and more willing to buy merchandise—but Jump didn’t view ecchi as part of its main identity and preferred to give it less spotlight compared to its biggest hits.

But the fact remains: this otaku subculture existed and had a large fanbase. Dating sims like Tokimeki Memorial, which sold 500,000 copies at its peak in the 1990s, and Love Plus, selling 250,000 copies in the 2000s, defined their eras and were referenced even in Shonen Jump works — Gintama even has an arc where Shinpachi gets addicted to Love Plus. So the audience was large enough that it existed and continued existing, transforming over time into fans of light novels and their adaptations in the 2000s, then into fans of mobile/social games in the future (Fate/Grand Order, Kantai Collection, Blue Archive, Uma Musume, Gakuen Idolm@ster, etc.).

Nue’s Exorcist won over fans precisely in this niche. Most comments from the beginning talked about how much the series embraces these concepts without shame and feels like something straight out of the Heisei era (1989–2019). Additionally, it’s a work of this type being published in Japan’s biggest manga magazine. It’s no coincidence that many authors involved with these movements, including Nasu himself, declared being fans of the manga.

Factually, Akiba culture did not have the same impact in shaping anime culture across most of the rest of the world, especially in the West. The very concept of the “Big 3” — One Piece, Naruto, and Bleach — is a purely non-Japanese construction. Although all are popular in Japan, they did not “popularize” anime/manga in the country nor dominate public perception of the medium.

Sure, people love One Piece there, but even casually, people knew there was a large segment of niche works for otaku.

With MangaPlus now releasing all Jump works in English simultaneously with Japan, some fans who associate the magazine exclusively or primarily with battle shonen developed a very negative perception of Nue’s Exorcist. “Lame,” “cringe,” “weird.” It’s not as if the manga is a unanimous hit in Japan, but from the beginning it gathered a large group of supporters — something that didn’t happen outside Asia.

This doesn’t mean we can generalize everything and everyone based on where they live. Personally, I liked battle shonen, but I dove into the more “otaku” side of the industry early; I watched Di Gi Charat on Animax (which features mascot Dejiko, an Akihabara icon shown in the image above) and soon fell in love with romcoms, following more shonen works in the genre like Hayate no Gotoku and Kami Nomi zo Shiru Sekai (The World God Only Knows) in my teens. At the same time, many Japanese readers don’t care for niche works and prefer Jump to focus on battles, since they’re the magazine’s most popular works.

Everyone has their own preferences and experiences — we cannot question that, nor the right for each person to like what they like. But the point here is that Nue already had a more receptive field in its home country for the type of work it openly is. Not huge, but enough to secure a safe stay in modern Shonen Jump, and also a type of audience more dedicated to buying merchandise seen as appealing to otaku consumers.

In less than three years of publication, Nue has already had pop-up stores, themed cafés, and is one of Jump’s most regularly merchandised non-animated series. In this sense, it becomes an interesting niche at a time when volume sales are declining across the industry. Jump will never abandon its desire to have the biggest battle hits, but it may be forced to give more space to “safe niches” in terms of profit. There is no mystery as to why the series continues, contrary to what many claim online.

UNIQUE QUALITIES

So does this mean Nue succeeds only because it brings nostalgia? Obviously not — if it were easy, every author would do it.

A common — and incorrect — talking point repeated in anime/manga circles is that “if you put cute/pretty girls in it, the author is pandering to succeed.” First, the most popular series are battle manga, so wouldn’t “pandering for success” mean focusing on cool battles? Second, even if this formula made sense, we have countless examples of series with sexy or cute designs that didn’t do well. As always, it’s a matter of execution. A good battle manga needs impactful scenes that grab readers’ attention, while a romcom needs interesting designs to stand out among many others.

In Nue’s Exorcist, the heroines’ designs attracted attention almost immediately, with numerous fanarts of practically all of them. From Nue’s design incorporating elements of ancient Asian clothing to Shiroha’s more traditional kuudere face, they work both for action moments and romance moments.

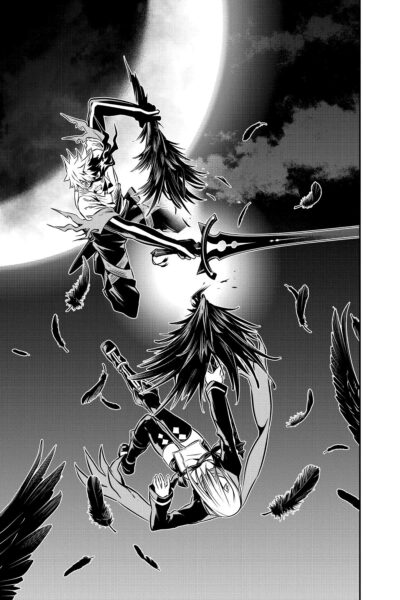

The battle art also stands out, with spirits that truly look alien compared to the norm, and with continuous evolution in paneling and battle art, where author Kota Kawae prioritizes a greater number of panels showing movement and actions over relying on big double spreads for impact.

Narratively, the story is essentially that mix of chaotic romantic-comedy “ordinary school days” with large-scale frantic action. It’s not the most unique concept ever, but as always, execution matters — especially for Japanese audiences that value the oudou concept: the divine path, implying that following “clichés” can be a valuable quality because the author dedicates themselves fully to executing familiar tropes well. It’s like attending a rakugo theater performance — you already know the story’s outline, but the way it’s told varies through the personal touches of each performer.

Of course, if the execution is weak, the manga will be torn apart for not bringing anything new and failing to make the classical elements work. This is a common criticism of Jump flops, including traditional battle series that failed despite following the formula closely.

An example of how Nue connected with readers in this sense is the Fujino arc early in the manga, which practically ensured its survival in the magazine. The first part of the arc focused on everyday romance and comedy scenes as Gakuro meets Fujino Shiroha, who entered the school to take Nue from him. The situations are silly but funny, like when the two go to a café together and an older mustached man randomly says “Marvelous” (in English) upon seeing them together.

It may be silly, but these everyday scenes pay off when the final clash between Gakuro and Shiroha happens and the protagonist declares he’s fighting to save her from her fate of being just a “tool” of the Fujino family, without her own individuality. Shiroha screams back that he’ll never understand, but he stands firm in his conviction. Japanese readers loved this and compared it to similar iconic moments in other works, like Touma vs. Misaka in To Aru.

Nue’s Exorcist balances both sides well so that Gakuro’s “defense of ordinary life” makes sense when facing big enemies. By allowing characters to be silly in daily life, readers grow attached to them because they exist beyond the boundaries of the Battle World.

A massive attack from a Hyo is more impactful when it puts at risk characters we’ve grown to like, rather than simply stating it “would destroy the city,” which carries no emotional attachment. A more intimate scale of conflict is a frequent storytelling tactic: Frieza killing Krillin generates a bigger reaction from the reader — now wanting to see Frieza beaten — than him “destroying planets” we’ve never seen.

As for the comedy, it is heavily praised, with many scenes going viral on Japanese social media even out of context. The whole classroom reacting to a new student and uniformly thinking, “Not everyone understands her, but I do,” is genuinely funny and became a regular meme online.

Nowadays, comedy-focused chapters, romance chapters, and action chapters are all well-received by fans. No aspect overshadows the others; harmony is essential for a battle harem to work — and striking that balance is difficult.

DISTINCT VOICES

Does this mean that every To Aru or Fate fan will like Nue? No!! Each work has its own quirks, and people’s tastes vary even within the same fanbase. Some people may love Fate for the concept of historical heroes fighting and care little about the romance. You cannot generalize everything.

I’m not saying every “hardcore niche otaku” will love Nue’s Exorcist, nor that a more typical battle shonen reader can’t be a fan of the series. I know people who love ecchi, romcom, VNs, etc. but don’t care for Nue, and battle fans who love the manga for its powers, fights, and even romance. Likewise, you can’t say “all Japanese like Nue” or “all Western fans hate Nue.”

However, it’s important to understand that the anime/manga industry is enormous and diverse, and many perspectives are limited in certain spaces. Unfortunately (or fortunately for some), there is a certain sentiment that some genres and styles are inherently inferior among some fans and parts of the media.

Within this, works aimed at the more niche otaku audience receive far less respect outside Japan, where — for the reasons explained above — the niche subculture has a larger fanbase and greater influence even within the shonen sphere. You could say the distance between a Jump battle shonen and a light novel battle harem is smaller in Japan due to obvious factors like accessibility, larger community sense, and historical development.

I’m not demanding anyone read Nue, dislike it, and think “Actually, it’s good.” But certain comments — like generalizing all Japanese readers as “only liking it because it has fanservice” — are completely senseless. You might not like Nue, but there are reasons it has survived for over 120 weeks in Japan’s most competitive manga magazine, and they are understandable even if you don’t agree.

Everyone has the right to their tastes, but opening space for more voices with different opinions — without belittling or silencing dissenting discussions — is important. Whether you like it or not, the part of otaku culture some people dislike is a huge part of what anime and manga are, and ignoring it means losing nuance in understanding the medium as a free artistic field.

This goes for many sides. When people use “fujobait” as something bad, or appear with bizarre takes like “just draw handsome men for fujoshi,” there is an attempt to ignore the depth of subcultures, as if their participants had no sense of quality or disagreement.

And the same applies to those who belittle battle shonen as “inferior” for being too mainstream, ignoring how much they influence even “cute girls doing cute things” anime. It’s an industry of many facets, and even its niches influence each other.

NUE’S JUMP

Recently, a tweet about the next generation of Shonen Jump went viral, featuring the works above: Nue’s Exorcist, Kagurabachi, Kiyoshi-kun, Hima-ten, Madan no Ichi, and Shinobigoto. The magazine had already announced this promotional campaign for its upcoming generation, with new products available in its official store.

Some comments were outraged: “How dare they put these others alongside Kagurabachi and Ichi?” But Jump has always been a magazine that offered both the biggest market hits and smaller successes popular among its readers. Pyu to Fuku Jaguar, a very weird gag manga, ran for 10 years in the magazine, surviving nearly the entire “Big 3” era. Part of running a weekly magazine is accepting that there will be different scales of success for different genres and styles, even if the editors still focus on finding the biggest battle hits.

Additionally, it’s a meaningless complaint when you analyze the numbers: the other four works will obviously remain in the magazine at least for the next year, since the number of failures is too high for any of them to be in danger. So the promotion is perfectly normal.

This ties back to the idea of not wanting to ignore the existence of everything we dislike. A deeper understanding of manga — both as art and as a market — requires seeing the full context it exists in. Maybe Jump will bet more on small niches like Nue as “bonuses” alongside its big hits; maybe it won’t, preferring to keep gambling on tradition. It’s something we’ll see in the future.

Curiously, I was in Japan during this campaign and visited the Jump store. As a Nue fan, I bought several products from the manga. When I went to pay, the Japanese cashier looked at me and happily asked if I was a fan of the manga, surprised. I said yes, he smiled and said he was a big fan too, showing me that he was wearing a Kyokotsu badge — a character from the manga.

Yes, Nue’s Exorcist fans exist.